|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Identity can be described as a subjective sense of wholeness. Ethnic identity is a part of this, and its development begins in childhood, when youngsters learn the labels and attributes of their own ethnic groups. Identity forming itself is a central development task of adolescence.

Psychologist JS Phinney roughly splits the development of ethnic identity into three stages:

Stage 1: Unexamined ethnic identity

In early adolescence, many individuals haven’t yet explored the meaning of their ethnicity in depth. Often, minority individuals initially internalise white societal values and standards and accept the values and attitudes of the majority culture, including the negative views.

Stage 2: Ethnic identity search

A turning point or crucial moment pulls an adolescent out of stage one. It could be catalysed by a shocking personal or social event that dislodges them from their old-world view and makes them receptive to a new interpretation of their identity. In this stage, adolescents express interest in learning about their culture and actively engage in doing so.

Stage 3: Ethnic identity achievement

Individuals have a clear, confident sense of their own ethnicity. They can deal with negative stereotypes and prejudice, coming to accept their culture and themselves.

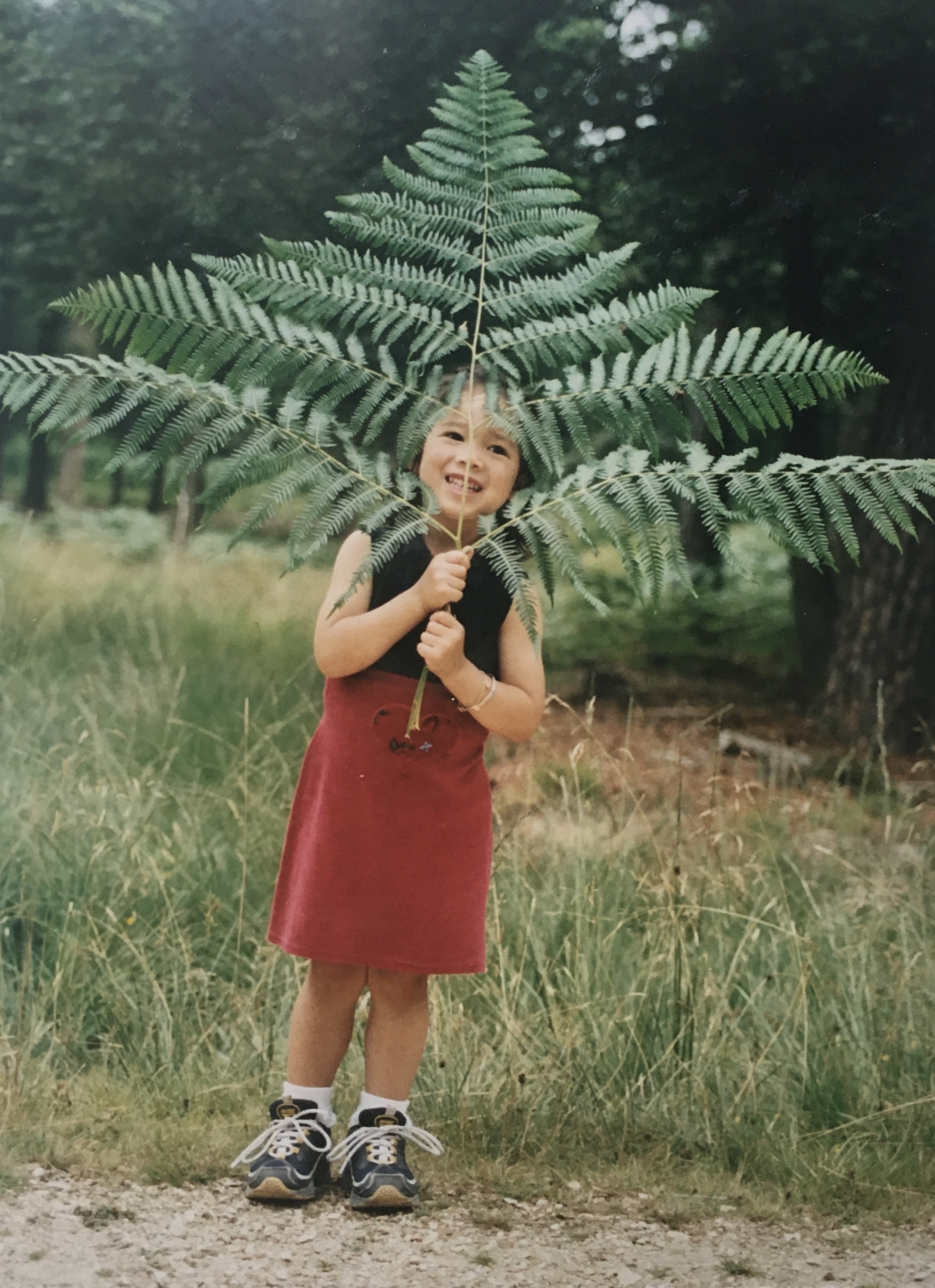

I can roughly see the stages of ethnic identity development mirrored in my own life. Half English, half Hong Kongese, I grew up in London in a predominantly white culture. When I entered nursery, English and Cantonese were both listed as my first language, but within a few years of being at school, coupled with my awful attitude to Chinese lessons, my Cantonese had gone rapidly downhill.

After I stopped learning Cantonese, my ‘Chineseness’ didn’t get much airtime, aside from occasional family visits and the food we ate. We loosely kept Chinese New Year and my mum tried her best to carry on speaking to me in Cantonese, but I was ambivalent. Growing up, I think I saw myself as ‘white’.

A Hong Kong friend recently said I am a classic banana: yellow on the outside and white on the inside.

While I’ve always been interested in my family history and

hearing stories from my mum’s childhood in Hong Kong, I saw this as very separate to myself, an irreconcilable puzzle piece that didn’t quite fit into the jigsaw I understood as my life.

Gradually though, small things began to add up which made me more curious about Chinese language, politics, history and culture. I went to uni and had more Asian friends. Over the summer of 2017, I worked as a residential tour guide for three visiting cohorts of Chinese students. I got to mix almost exclusively with large groups of Chinese people my age for six weeks, and it made me want to explore what felt like a whole half of myself I had thus far neglected. In 2019, I visited Japan. I was utterly entranced by the vibrant culture, so different to the one I had grown up in; and being able to read some kanji characters made me want to learn Cantonese again.

In March 2020, I went to Hong Kong for the first time since I was a toddler. I felt strangely at home: when I was alone, shopkeepers spoke to me in Cantonese, and I felt as though I understood myself a bit better after seeing and experiencing some of the culture my mum had grown up in.

A key moment for me happened a short time after the tragic murder of George Floyd, which catalysed conversations about race. A friend made a passing comment about me being their ‘Chinese friend’ and it being funny because they weren’t usually friends with Chinese people. They also felt the need to clarify that I wasn’t like ‘most Chinese people’. I’d never really felt my non-whiteness as keenly as in that moment, when it was brought up by someone I had known for years.

I had been so firm in my understanding of myself and all my vastly western experiences, that I hadn’t thought my ethnicity might be seen as a defining part of me for the people I knew best, when it didn’t feel that way for me.

Of course, there had been comments before from strangers and acquaintances: the odd thing shouted in the street, mentions of my ‘exotic’ skin colour or features, and work colleagues I had only ever emailed being surprised I was ‘not white’ (“you have such a white name!”) when we first met face-to-face. But these hadn’t made me reflect on my ethnic identity nearly as much as my friend’s comment.

I’m still growing into my ethnic identity. I think I’m

reconciled to the fact that I have some things different and in common with each of my parents, as well as my own unique experiences. I know I want to celebrate and understand my Chinese side more: I’m learning more about the culture and traditions, and I’m endeavouring to keep up learning Cantonese – though it sometimes feels like a losing battle!

I want to learn more about these things because I want to understand and feel proud of the things that make me, me. I hope I can continue to grow until I reach my ethnic identity nirvana.

Our understanding of our ethnic identity is, of course,

something intensely personal. While the stages of ethnic identity development emphasise the importance of individual exploration, questioning and soul-searching, they also highlight the power of the collective. In Stage 1, this can be positive: particularly proud patriotic parents can give early adolescents an optimistic outlook on the group, or negative: when a majority group’s prejudices are internalised by a minority.

I certainly think this highlights the importance of fora like multippl – even if you ultimately shy away from group identity, a community where we can share views and experiences can help us all move to a better understanding of our own ethnic identity, and therefore a world that is more tolerant and celebratory of both similarity and difference.