|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

I like to think growing up bilingual led me to pursue the study of languages. Or maybe it was the D I got in AS Maths and the consequent realisation that I was hopeless at every other subject?

Regardless, I had always ‘excelled’ (i.e. didn’t do as badly) at languages throughout school, prompting me to undertake a degree in French and German at University in an attempt to become quadrilingual.

Jump ahead to

Being bilingual

It has often been said anecdotally that bilingual people develop an enhanced cognitive ability that makes them better at acquiring languages. Bilingual households can be mentally demanding environments, especially if you’re like me and alternate between languages within a sentence.

A recent conversation with my mum sounded something like this:

Me: Raishuu tube strike aru mitai (Looks like there is a tube strike next week)

Mum: Aso, dousuruno? kaishaniikuno? (Oh really, what will you do? Are you going to the office?)

Me: Maybe, my manager says dekireba kite (Maybe, my manager says it would be good if I could go in)

Mum: Demodouyatte ikuno (But how will you get there?)

Me: Saa (Who knows)

The bilinguals among you will recognise the linguistic nightmare. There is a scientific basis to the idea that bilingualism can fundamentally change your brain, and there’s a plethora of research exploring this.

Bilingualism and learning new languages

Fewer studies directly investigate the link between bilingualism and learning languages, but one such piece was conducted at Georgetown University.

To examine a potential relationship, an artificial language was constructed and presented to two groups of students; one consisting of monolinguals, and the other of Mandarin-English bilinguals who had grown up speaking both languages.

The artificial language bore no similarities to either language to prevent any previous knowledge influencing the language acquisition process.

Upon analysing the brain patterns of learners studying the artificial language, researchers found that after just the first day of training, a brain-wave pattern was observed among the bilinguals that is commonly seen among native speakers when processing their own language.

Among the monolinguals, however, this brain-wave pattern only began to emerge towards the end of the training and furthermore a separate brain-wave pattern could be seen which is not typically seen among native speakers of languages.

The art of language

Language is much more than the science of brain functioning, though, and it is the ability of language to act as a key to different cultures that encouraged me to pursue their study.

Having a childhood divided between the UK and Japan led to an exposure to a variety of cultures, particularly as I also attended The British School in Tokyo, an international school, during my time in the latter.

This exposure undoubtedly piqued my interest in languages and learning more about other cultures.

Language and culture

These can often go hand in hand and languages alone can teach you a lot about a country, its culture and its people.

For example, politeness and respect are fundamental aspects of Japanese culture which stem from the strong emphasis placed on the hierarchical structure in society.

Humility and showing respect to your elders and superiors are deeply ingrained in the Japanese mindset. Even between strangers, a degree of formality is expected.

We see this reflected in the language through the presence of different of polite language – keigo (敬語), sonkeigo (尊敬語) and kenjōgo (謙譲語).

The challenge of multilingualism

When you’re bilingual or even a polyglot, problems can emerge though, particularly when you carry different linguistic customs into other languages.

For example, when addressing someone as ‘you’ in French, according to the level of formality you’ll either tutoyer (address someone as ‘tu’) for informal conversations or vouvoyer (address someone as ‘vous’) in a more formal setting.

On one occasion I found myself writing a message in French to a friend of a friend (i.e. someone I’d never met). Unsure as to whether to tutoyer or vouvoyer, my Japanese mindset felt it was only right to verge on the side of politeness.

Much to my dismay, this decision was met with mockery as I was ridiculed for being ‘overly polite’.

Exploring linguistic determinism

Every language is limited to a set of grammatical rules and vocabulary. In this respect, not only do languages shape how we are able to express ourselves but also influence our mindset – a concept known as ‘linguistic determinism’.

Among bilingual people, it’s often been noted how this bilingualism can almost manifest an alter ego when speaking in the other language. Indeed, Charlemagne is thought to have said “to have another language is to possess a second soul”.

This is no exception as a Japanese/English speaker. Due to the nature of the language, I often find my ‘Japanese-self’ to be (in general) more ‘wholesome’.

You could argue that much of this disparity is shaped by who I tend to use both languages with. Most of my close friends are English-speakers and even among fellow-half-Japanese friends, the preferred method of communication is English.

In contrast, I tend to only use Japanese when speaking to my mother, mothers of friends and relatives. That’s not to say Japanese is devoid of informal or crude speech.

Although when asked the inevitable “what’s a swear word in Japanese” by non-Japanese speakers, the best response I can usually muster is “aho” (idiot). No ice needed for that burn…

Multippl and multilingualism

Growing up bilingual, we are privileged in having the opportunity to acquire a language from each parent – but it’s not always smooth sailing.

It isn’t uncommon for bilinguals to have a dominant language. I’m no exception – my level of English greatly exceeds that of my Japanese.

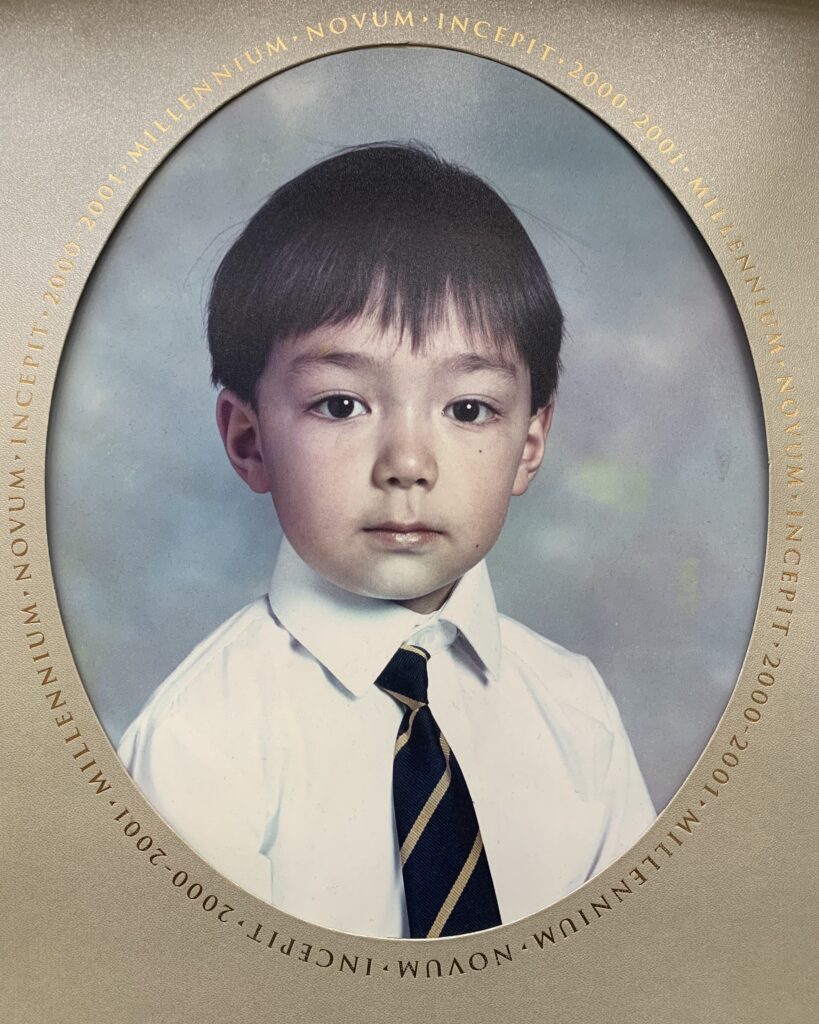

Memories from a particular day still torment me from time to time. In contrast to the current state of affairs, at this stage of my life I was at school in England but only spoke Japanese.

The language barrier unfortunately meant I could not communicate my request for permission to go to the bathroom. I’ll spare you the details, but it was a messy clean-up operation.

In my defence, I was only four years old. I would apparently often come home in tears out of frustration of not being able to communicate.

If you’re a fellow ‘multippl’, I’m sure you’re also well aware that growing up bilingual isn’t as simple as subconsciously acquiring a language.

While you do possess an advantage, it still requires hard work. I envied my English friends who weren’t forcibly made to learn a seemingly endless number of kanji (Japanese characters).

But would I trade that for monolingualism? That would be a kakujitsu na (definite) no.