|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

There are two certainties in lifeー death, and taxes, right? Even though we know death is inevitable, we try to turn a blind eye from it, right? When we were kids, we all imagined that when we grew up, technology would advance to the point that we can live forever, right? The Queen was meant become a centenarian and write herself a congratulatory letter, right?

Jump ahead to

Queen Elizabeth II

As Great Britain and the Commonwealth mourn the death of its matriarch, Queen Elizabeth II, London cries. As Great Britain loses its longest serving monarch – she was on the throne for 70 years – there is no doubt that her legacy will live on; in the form of personal memories, audio, video and photos.

Speaking to my British grandma on the evening of the day The Queen died, we reflected on her legacy, starting with a story of her coronation. My grandma was 12 years old when she was invited by family friends to see the coronation. It was the first time she had ever seen a TV – black and white, of course.

My grandma said: “She will be remembered forever and ever for being dutiful, upholding the dignity of Britain. She was loving and caring to the whole world”. My grandma also reflected on the time she met Queen Elizabeth as she got off the train at Totnes station. She uttered the words, “Welcome to Totnes your majesty”. To which The Queen responded, “Oh thank you veh much my dear”. Legacy.

But the inevitability of death never fully prepares us for the loss of a loved one. In June, I learnt this all too painfully myself, when we lost my Japanese obachan (grandma). Through telling a brief story of her and the funeral, I will explain the main differences between a Japanese ososhiki and a British funeral. Japanese vs British Funerals.

Obachan (Grandma) – growing up

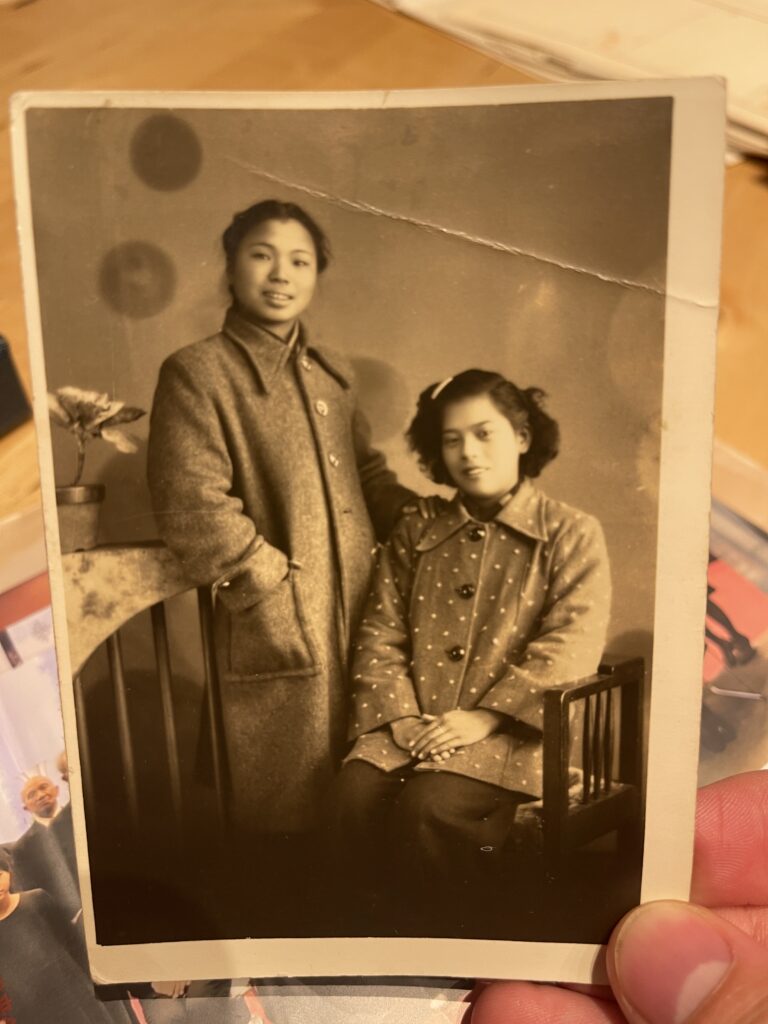

Isako Nakamura, my mother’s mother, was born the eldest of six children in a city called Shibetsu in Hokkaido (the most northern Japanese island) on 10 July 1934. However, her mother forgot to get the birth certificate authorised so her ‘official’ date of birth was 10 December 1934. Tomesaburo, her father, had migrated from Wakayama, a prefecture next to Osaka and Nara, to be an agricultural cultivator.

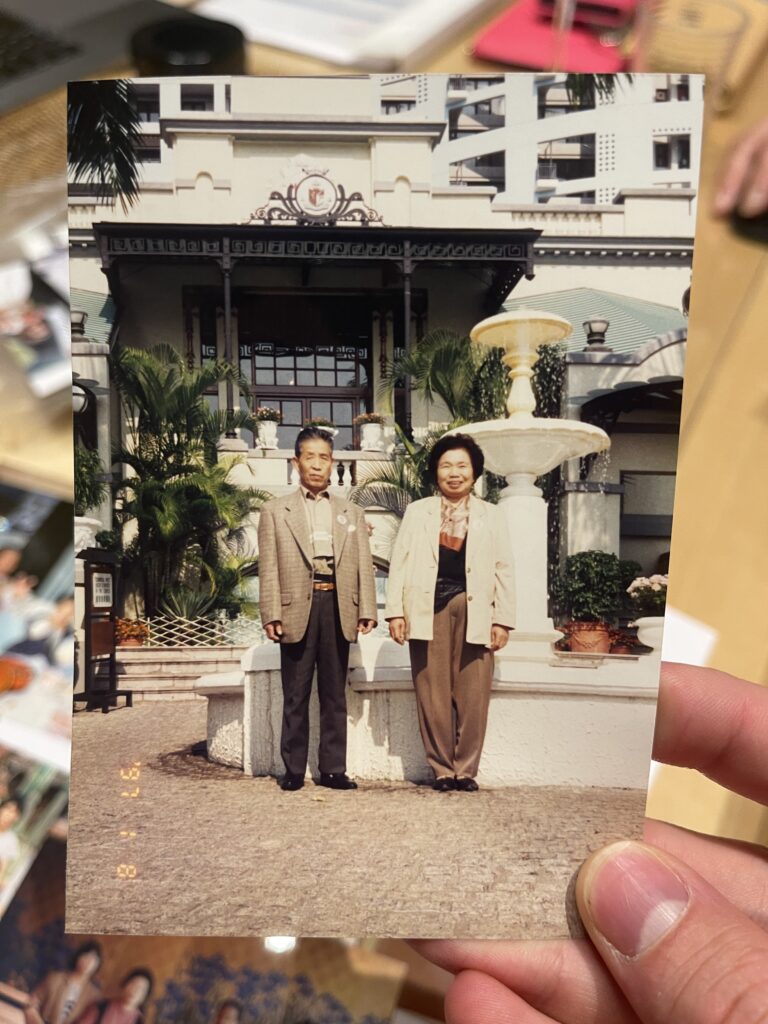

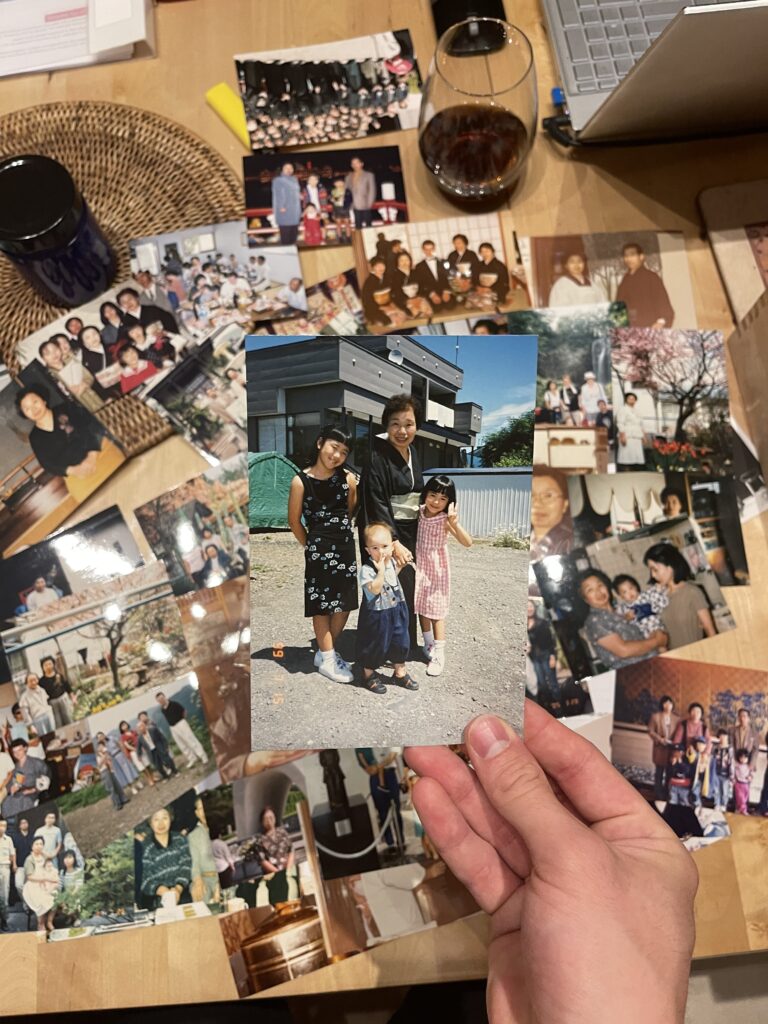

My obachan lived most of her school years in Shibetsu. After getting married to my grandad Tamotsu (1929-2013), she moved to Sapporo, the capital of Hokkaido. There, they started working in a flower shop owned by a man called Miyamoto. They bought a house next to the flower shop that they owned and lived in until they both passed away. There they had four children. My mother is the eldest and was born in the house.

Obachan

Obachan (grandma) was an earnest, religious and hardworking woman who had love and kindness in every inch of her body. When my British father first went to Japan, he was the first Caucasian my grandparents ever met. They could not communicate with each other because of the language barrier. In most situations, this would end in awkward silence and a difficulty to create a rapport. But obachan showed her love and kindness by making my father food. With the language and customs barrier my father did not know how to say no. He had to wait until my mother came home from work.

I’m proud to remember and write about my obachan’s open-mindedness, her ability to look past race, and the warmth of love that chased away any awkwardness of a language barrier with my father. I was lucky enough to go to Japan every summer when I was growing up. I spent weeks in the house in Sapporo learning all about my ‘other’ side; she would always make sure I learnt Japanese customs and rituals. These are very important and there are many in Japanese culture, including during the ososhiki (funerals).

Saying goodbye

On 10 June, a month before her 88th birthday, my mother messaged me with heart sinking news about my obachan. I was at journalism school and was overcome with emotion. I hoped I could go to her funeral to thank her one last time for everything she had done for my family and for me; teaching and developing my Japanese side. Joji had just released Glimpse of Us and it will eternally be the song that reminds me of that day.

Alas, due to Japanese COVID-19 rules and the cost of flights only my mother was able to go. The funeral was scheduled for three days later, on Monday. My father and I joined by Zoom.

Funerals are an act of love towards that person, giving friends and family a chance to say goodbye, express their grief and acknowledge the death.

Japanese Ososhiki (Funeral) Traditions

Japanese ososhiki are unconventional to the unaccustomed and offer valuable insight into Japanese customs and ritual, and are often led by a mixture Buddhist traditions and Shinto (or whatever religion the deceased believed). Due to a lack of space in Japan 99% of funerals involve cremation. Ordinarily, local governments and graveyards prohibit coffin burials. But it isn’t impossible and can be organised if it is more suitable to the deceased and the family beliefs.

If possible, the body of the deceased is brought back home to spend one final night there. Ice is packed around the body in the casket to prevent decay. This is one reason for the speed of Japanese funerals – three days for my obachan. People are then invited into the house to give their condolences.

The next day, the body is taken to the funeral home or temple, where the services take place. Both my grandad and grandma had their services at the same funeral home that combined the service, overnight lodging and cremation all in one package. When the body arrives at the home, it is placed in front of arrangements of lights, sculpture and flowers. Then the otsuya – or wake – begins.

Otsuya – Wake Ceremony

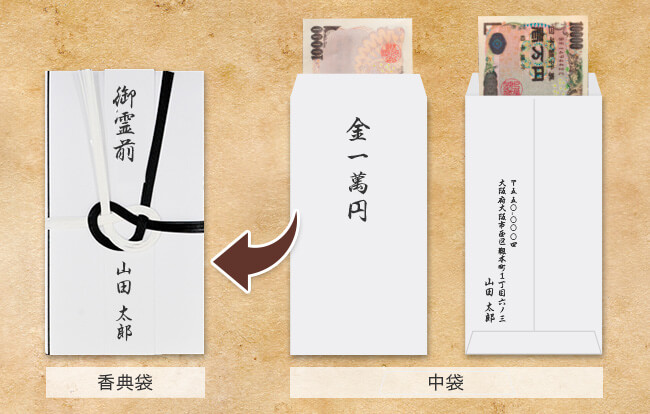

The otsuya, meaning pass the night, begins on the evening of the eve of the funeral. Attendees are not expected to wear formal black clothing. Guests will bear gifts of money sealed in special envelopes called kouden bukuro. The amount expected to be contributed will depend how close you are to the deceased. Money is the normal gift given by the Japanese instead of presents or flowers offered elsewhere.

Anyone who is not immediate family will then leave to allow for the night’s vigil. Here, the family will have a last supper with the body that includes light hors d’oeuvres, sushi and alcohol. The head of the deceased’s household will give a toast and shout kenpai (funeral version of kanpai). The family will talk about the memories they had with the deceased. Some stay up with them for one last night; others go to sleep for the funeral service the next day.

Ososhiki (Kokubetsushiki) – Funeral Ceremony

The expected colour to wear is black and it is more formal than the night gone-by. The day of the funeral usually consists of three parts: the funeral service, the kokubetsushiki and the cremation. The service will depend on the deceased’s faith, but often a priest will say prayers accompanied with incense rituals.

The kokubetsushiki is when the guests will go up and pay their respects and offer condolences to the family. Once the sohiki and kokubetsushiki ends, the casket is opened. Flowers are given to the family and guests to place on the body. Once the casket is covered, the body is taken to the crematorium.

Kasouba – Cremation

At the crematorium, the family pay final respects before the body is put into a stove and cremated. The procedure usually takes an hour and a half. During this time, the guests and family have a final funeral meal together at the crematorium. When the fire has finished burning, the crematorium staff take the family into a private room and explain the bones, pointing out indicators of disease and effects of certain medicine.

Kotsuage – Ceremony of transferring cremated bones to an urn

If you are not familiar, it is extremely bad manners to pass something between chopsticks, and it is because of this ritual. When the body is returned from cremation, the family gather and pick up the bones together using special chopsticks (one bamboo, one willow to symbolise the two worlds) from feet to head and put the bones inside an urn. The feet are put into the bottom of the urn, and the head of the deceased’s family will start collecting the bones. Once the bones have been collected and the urn fills, up the body is then taken to the family home.

Memorial services and Obon

Depending on religious denomination the memorial ceremonies are slightly different. In Buddhist funerals, the urn is set on the altar and will remain at home until it is interred at the family ohaka (grave) on the 49th day. Modern gravestones are vertical made from black/grey stone with only names written on them.

The Japanese visit family graves during Obon, a three-day festival during the second week of August to honour the ancestral spirits. During the festival, families visit family graves, clean them, bring fresh flowers, incense, their favourite food and offer prayers. The wonderful thing about Obon is that ancestors are brought close to home every year with the Bon Matsuri and the famous Bon dance. The next time I go to Japan, I cannot wait to go to the family grave and give my thanks to both my Japanese grandparents who gave my family so much.

Japanese vs British Funeral Similarities

While there are some similarities in funeral customs between the UK and Japan like the black formal clothing, family and loved ones taking focal point and having a wake, there are vast differences coming from the difference in official religion. The Japanese funerals follow Buddhist ritual and customs while in the UK, most funerals will follow Christian rituals and customs.

British (UK) Funeral Arrangements

The first difference to point out is the length of time between passing away and the funeral. In the UK, the average time is one-to-two weeks after death. This could be due to any number of reasons including a coroner’s inquest, travel arrangements, or lack of availability.

British (UK) Burial ceremonies

In the UK, there is a choice to have a burial or a cremation service. There are many types of burial ceremonies, ranging from traditional cemetery burials to woodland burials and burial at sea. Some choose to circumvent all ceremony and opt simply for a direct burial.

British (UK) Cremation ceremonies

According to the Cremation Society of Great Britain, roughly 80% of burial arrangements in 2019 involved cremation. Once the cremation takes place, instead of being interred in a grave the family may decide to keep them at home or scatter them at sea, on a beach, at a park. Funeral services can take place at a crematorium, alternatively that may take place at a church or another place of worship and then have a shorter service called a ‘committal’ at the crematorium.

Funeral Procession and Funeral Service

On the day of the funeral, a hearse containing the coffin of the deceased will drive them to the crematorium or place of worship. The hearse will be followed by a procession of cars going to the funeral with the closest family member leading it. Many guests will not participate in the procession and will arrive at the venue for the funeral. Guests offer flowers, a memory or story they have of the deceased, a card instead of money given in Japan.

A funeral service takes around 30-45 minutes, including arrival and departure. The coffin may be placed on a catafalque before the funeral or carried into the venue by pallbearers. Pallbearers can be provided by funeral directors or alternatively people close to the deceased.

Celebrants

The funeral service is officiated by a celebrant who are often religious figures such as a priest or minister. The funeral celebrant helps plan an order of service and ensure that it reflects how the family want the person to be remembered. A funeral service is very personal but will usually include a eulogy, funeral hymns, readings including funeral poems and slideshows of pictures and videos provided by family and friends.

Post Funeral Service – Cremation

After the service, the coffin is usually obscured by a curtain as it is transferred to the cremator and a song is played. This is usually called the committal. After the committal, mourners are invited to look at funeral flowers or notes. It is possible to view a cremation, but it must be arranged in advance and unlike Japan there is no meal while the mourners wait to see the bones and ash.

Post Funeral Service – Burial

If the deceased is to be buried, pallbearers will carry the coffin out of the church and return it to the hearse for a second procession to the cemetery. Once at the burial ground, the coffin is removed from the hearse and placed on planks above the grave while all mourners gather around it. The celebrant will say some words before the coffin is lowered into the grave by pallbearers.

Funeral Reception or Wake

After the funeral, families choose to have a funeral reception so mourners can gather and reminisce on the life of the deceased. The reception which is sometimes called a wake may happen immediately after the funeral or a few hours later. It can be at the family home or any venue available for the number of mourners. Funeral receptions can also occur on an anniversary or when the ashes are scattered.

After the Funeral

With that, the British and Japanese funerals come to a close. Most guests will carry on with their lives, but for some the process of grief will have only started.

On the day of Queen Elizabeth’s death, I asked my British grandma how she has dealt with grief over the years. She thanks having a faith that allows her to find a sense of peace and think of all the happy memories and good things the person gave her.