|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

“What do I count as?” My brother’s pen hovers over the tick boxes for race on a diversity and inclusion form. The list is not comprehensive.

“Chinese?”

“We’re not really Chinese.”

“British?”

“We’re not really that either.” I find myself saying, “Just put ‘other’.”

For individuals of mixed ancestry, including half Asians like myself, this feels like a common question: what do we count as, where do we fit, where do we belong?

We can’t be grouped into the conventional, tidy compartments of race. Instead, we sit somewhere outside them — or between them — or somewhere separately altogether as a group of our own.

Far from being a modern crisis of self-understanding and identity, eluding conventional racial categorisation is a feature of a shared history, right back to when the first mixed White and Asian — Eurasian — baby was born.

Jump ahead to

The first half Asians

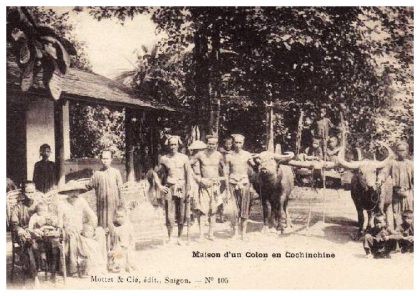

In the 16th century, European powers began to turn their gaze towards the East, and colonial hands reached out for trading footholds and access to rich Asian markets. The Portuguese were the first dominant imperial power in Southeast Asia, establishing their presence with the capture of Malacca in 1511. It’s likely that the first Eurasians (half Asians) were born around this time. As other European powers developed power bases in Asia; the British, Spanish, Dutch and French all had colonies in the Far East, so the number of people of mixed European and Asian ancestry increased.

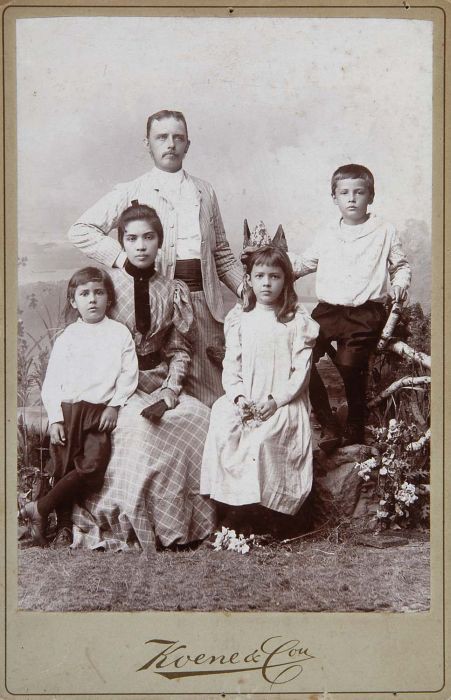

Contemporary writers were quick to say that cross-racial relationships were the result of anything but attraction or love. One writer observing the British colonial experience in Burma claimed that native women helped acclimate European men to their new Southeast Asian settings, and their sweeter and more affectionate personalities meant British men could not help themselves. Eurasian offspring came about because of the necessity for female companionship, rather than anything more. Even in instances where indigenous women and European men were married, the writer refuses to acknowledge native women as wives, suggesting that British men had no option but to lower themselves by being with an indigenous woman before they could return home and find a suitable woman.

Most Eurasians in colonial society were born to an indigenous mother. Though rare, relationships did occur between indigenous men and European women. In the Dutch East Indies, 40 marriages between European women and indigenous men were recorded in a decade, but these handful were sufficiently worrying to bring about the 1898 Mixed Marriages Act, which codified that a woman would lose her nationality and legally become a ‘native’ upon intermarriage. Similar attempts to discourage racial interbreeding were a present in European colonies right into the 20th century, notably in Hong Kong.

The Eurasian role in the colonial machine

As an ‘in-between’ group, half Asians were simultaneously discriminated against and privileged. A western education, coupled with indigenous cultural and linguistic knowledge, meant colonisers relied upon Eurasians to rule and they often held important positions as intermediaries. Some performed the function of go-betweens — as highly-prized translators, interpreters, and compradors. A small group played a significant role in the power politics of colonial Asia as cultural brokers in a relationship between European administrators and indigenous people.

Eager to reap the benefits of this cross-cultural knowledge while ignoring as much as possible the mixed blood that enabled it, colonial administrators awarded Eurasians who more closely resembled Europeans better jobs. This created a hierarchy within Eurasian communities based on their ‘whiteness’ and many made attempts to improve their position by imitating their colonisers.

Not all Eurasians excelled by virtue of their mixed blood. Not clearly fitting into one society also had its drawbacks, and meant individuals were rejected from some jobs and events. Eurasians were distrusted from all sides; for having a different identity in the first place, but not really having an identity at all. By being a chameleon, and neither one thing nor the other, Eurasians were stereotyped as sneaky and opportunistic and were treated with derision and suspicion by both Europeans and Asians.

Even those who excelled in business and colonial administration were never fully accepted and were at best seen as ‘blurred copies’ of the European ideal. European citizenship, which was granted to some Eurasians, was still not enough to be considered a ‘real European’. Nevertheless, the rise of Eurasians in colonial authorities, coupled with some individuals’ business success and eventually improved social status, provoked discrimination and a degree of prejudice against the whole community.

A cat among the pigeons

Half Asians’ intermediate status was seen as a destabilising challenge to traditionally clear-cut racial boundaries. For native Europeans, mixed blood children symbolised shameful liaisons with native women. Similarly for Asian communities which hold strict ideas about ancestry and lineage, Eurasian children were scorned and seen as bastards.

For the European colonisers, though, Eurasian children also represented something much more significant.

The British did not know how to racially classify half Asians in a way that was not an ideological contradiction to their colonial narrative. The construction of ‘race’ was crucial to the colonial project. European-ness, whether Englishness, Frenchness or Dutchness, was defined in stark contrast with the colonised ‘other’: ‘They’ were everything ‘we’ were not. The European coloniser was at the top of this racial hierarchy, the ‘civilised’ opposite of the native peoples. Mixed European and Asian children straddled the two conflicting worlds of the coloniser and the colonised and undermined the view that Asians were inferior to Europeans. Eurasian children and the perceived potential of interracial marriage to corrode the colonial racial hierarchy terrified many Europeans.

To maintain their racial hierarchy, the British set about establishing the inferiority of Eurasians — describing them pejoratively and propagating dubious science which suggested that human ‘hybrids’ were inherently unstable, lacked endurance, and were exaggeratedly vulnerable to disease and other debilitating physical conditions.

Other colonial powers pursued different methods when facing the Eurasian ‘problem’. Eurasian children in French-controlled Indochina who did not have a French father or French cultural influences were labelled as ‘abandoned’, despite living with their mother in their maternal society. Children who could pass as White but had been ‘corrupted’ by Vietnamese culture were seen as a threat to White prestige, and Eurasian children, by virtue of the dangerous combination of a debauched Vietnamese mother and the Vietnamese cultural environment, were considered predisposed to social deviance. The French colonial administration feared that this predisposition, coupled with anger at being denied the privileges expected of an individual of part European descent, would be channelled into a rebellion. To resolve this problem, non-governmental welfare agencies in French Indochina operating from the end of the 19th to the mid-20th century forcibly removed Eurasian children from their Vietnamese mothers. They were taken away so they could be transformed into Europeans, thus neutralising the threat of rebellion.

The construction of colonial Eurasian identity can be seen as an exercise in empire building. The 20th century philosopher Michel Foucault postulated that categorisation does not describe a social order and instead, categories like race, gender and class are regulatory ideals created to discipline, govern and shape power relations. Perpetuating these categories reinforces stereotypes of performative power and legitimises differences between groups.

Post-colonial half Asians

When colonisation came to an end, Eurasians found themselves in a difficult position. Their status had been based on European rulers, which were now gone, and indigenous rulers regarded them as colonial remnants and sometimes as traitors. It is on this chaotic and sometimes even violent backdrop that Eurasians had to decide where they belonged: in the country of their European fathers, or the country of their Asian mothers.

Modern half Asians — modern challenges?

I am a product of colonialism. My mother, born in the British colonial dependency of Hong Kong, moved to the UK with her family seeking better opportunities. It’s probable that many other ‘mixed White and Asians’ — almost 350,000 in the UK were recorded in the 2011 census — share similar stories of their ancestry.

My own experiences seem to loosely mirror those described in colonial history; feeling caught between two vastly contrasting cultures, not European enough to be European, but also not Asian enough to be Asian. This does have its benefits, and the malleability of Eurasian identity is a powerful thing. This racial fluidity turns out to be the oldest trick in the book.

Eurasians living in colonies who could pass as either a ‘pure’ European or Asian often would, rather than dice with the complexities and prejudices of acknowledging mixed blood. The Hong Kong census at the turn of the 20th century records a surprisingly low number of Eurasians (fewer than 300) and notes that many more will simply have categorised themselves as Chinese. The actions of Eurasians to conceal their race and defy the strict colonial racial hierarchy not only subverts racial performances, but also calls into question its foundations at a more fundamental level. To accept the concept of ‘mixed race’ first relies on accepting the notion of ‘race’ as real, rather than as a constructed idea.

In the 21st century, conversations about race continue, but (mostly) for the purposes of inclusion, rather than exclusion. In a world of positive discrimination and diversity box ticking, where do Eurasians sit?

How do we reconcile a group which may straddle both majority and minority groups with a label like ‘Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic’? And should someone who isn’t me be able to make a decision on whether I fall into that category — based, potentially, on what I look like, what my name is, or how I speak?

Employers may use Eurasians as a way of ticking the diversity box without really ticking it.

Onwards for chameleons

Today, the chameleon nature of half Asian identity is alluring.

While old social prejudices have largely, though perhaps not entirely, disappeared, Eurasians still face familiar problems with identity, marginality and assimilation. However, the very thing that once raised fear and suspicion in colonial leaders and natives alike — the ability to transgress racial boundaries and bridge cultures — is something that we now celebrate.

Like other mixed groups, Eurasians defy a ‘one size fits all’ racial identity. Our differing perspectives reinvigorate conversations and understandings of race and continue to facilitate progress toward a racially egalitarian society.

As we construct and reconstruct our own race in our daily lives, it’s not because we fear prejudice, or that to be one or the other would necessarily define our life chances. Instead, perhaps, it’s because the total is greater than the sum of its parts.