|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Jump ahead to

Art Prevails

In 1923, Isamu Noguchi enrolled at Columbia University, New York, to study medicine. It was here that he first met someone with the same surname as his estranged father; Dr. Hideyo Noguchi, the prominent bacteriologist whose portrait can be seen on the 1000 yen note. He told Isamu about his father and urged him to pursue the arts. Hearing about his father for the first time had a profound effect. Ultimately, Hideyo’s encouragement, coupled with that of his mother, redirected Isamu to art.

Isamu started night classes at the Leonardo Da Vinci Art School in New York. He trained under school head, the Italian Onorio Ruotolo, who immediately took a liking to Isamu’s work. After holding his first exhibition, Isamu dropped out of Columbia University to pursue full-time sculpting. This was when he changed his surname from Gilmour to Noguchi.

Fast forward to the exhibition of Isamu’s work in the Barbican, London, earlier this year. We were told by the receptionist to go upstairs, through the rooms in a clockwise motion and view downstairs. This way, you were able to chronologically see the evolution of Isamu, his artwork and how it was influenced by his various teachers and the places he visited.

In 1926, Isamu attended an exhibition and was inspired by the Romanian modernist master-sculptor Constantin Brâncuși. With a Guggenheim Fellowship, Isamu travelled to Paris and worked under Brâncuși. In Brâncuși’s studio, he learnt the principle of truth to materials following Brâncuși’s direct carving methods of wood and stone. However, he disagreed with Brâncuși’s ideal of pure abstraction and he turned his efforts to the natural world.

Worldly Inspirations

A citizen of the world, Isamu travelled around the world to countries in Europe, Asia and North America during the 1920s and 1930s. In London, he read up on Asian philosophies, art and religions, and in Beijing he learnt traditional ink-brush techniques. From his experiences, he concluded that “all Japanese art has roots in China.” In February 1931, after 14 years apart, Isamu finally met with his father Yonejiro in a hotel in Tokyo. However, following Imperial Japan’s invasion of Manchuria later that year, Isamu moved back to America.

A Life of ‘Self-Discovery’

The Boy Looking through Legs (1933) is a self-portrait of the artist looking the world upside down and was my personal favourite. Noguchi reflected on his global travels as a process of ‘self-discovery’: ‘I had to know my own identity and continuity.’ Even though he went through such adversity growing up, it is nice to think that he satirised his own life in this piece.

War and Political Activism

In 1941, Imperial Japan attacked Pearl Harbour, Hawaii, bringing the Americans into the Second World War. Then-President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 and imposed martial law. Consequently, all Japanese citizens and American citizens of Japanese heritage living in the western United States were forcibly imprisoned.

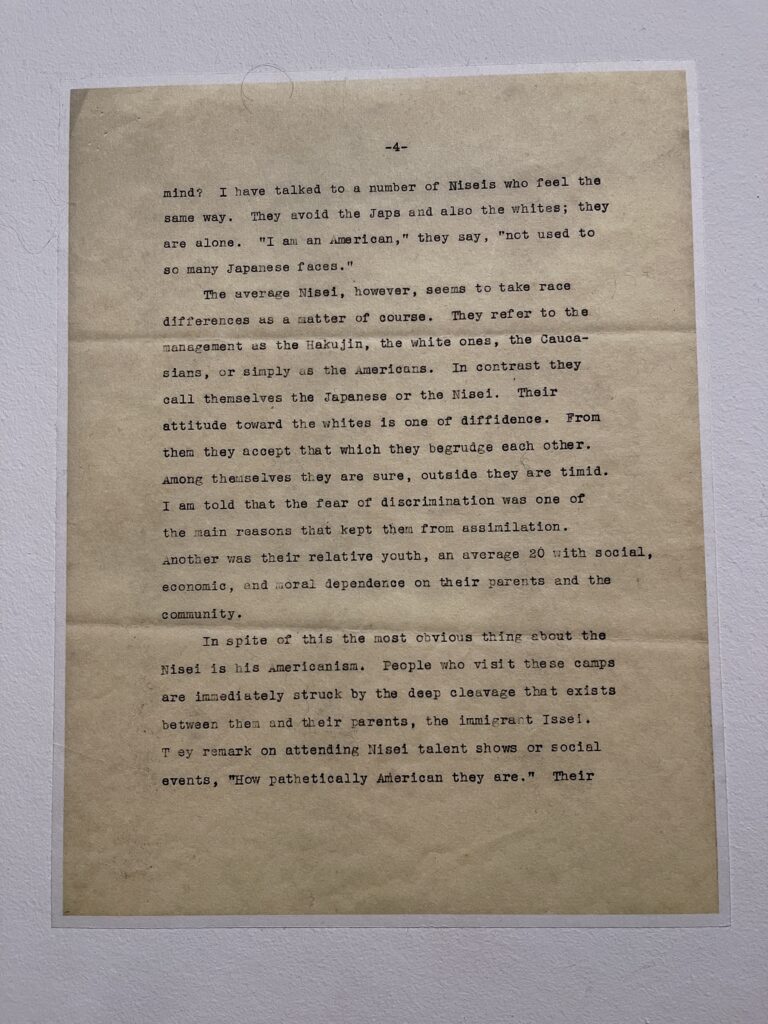

By then, Isamu had become a political activist. In 1942, while anti-Japanese sentiment was growing, he formed the antifascist group Nisei Writers and Artists for Democracy. He was quoted saying “I was no longer the sculptor alone. I was not just American but nisei. A Japanese-American.” Nisei: second-generation children who were educated in America to Japanese immigrant parents. He wanted to show solidarity with Japanese-Americans, while also proving that they were by their side. Although his efforts to join government departments were dismissed, he did meet a man who persuaded him to travel to an internment camp to promote arts and crafts.

Although exempt, living in New York, Noguchi chose to enter Colorado River Relocation Center in Poston, Arizona. The date was May 12 1942. Once again, he was not really accepted. Camp administrators accused him of being a troublesome interloper and internees did not trust him and thought he was a spy. Furthermore, he found nothing in common with Nisei, who regarded his as a strange outsider. In memoir/diary titled ‘I become a Nisei’, Isamu reflects on his experience at the camp but also his thoughts and experiences with Nisei.

He fears for their future as, “I begin to see the peculiar tragedy of the Nisei as that of a generation of transition accepted neither by the Japanese nor by Americans. A middle people with no middle ground. His future looms uncertain. Where can he go? How will he live? Where will he be accepted? Will he be permitted to remain?” Although talking about Nisei, perhaps these are thoughts that he once thought about himself.

This experience at the Colorado River Relocation Center had a profound effect on Isamu’s life and practice. Particularly seen in a series of works called ‘Lunars’. My Arizona (1943) and Yellow Landscape (1943) conveyed the inner turmoil and prejudice he experienced as an Asian-American. His Lunar series featured lights and were a precursor to his most famous Akari (meaning light in Japanese) light sculptures. A combination of traditional washi paper and technology in the form of electric bulbs sculpted households around the world.

Turbulent Family Life

After the devastating atomic bombs were dropped on Japan in August 1945 and the war ended, Isamu contacted a newspaper to know about his father’s wellbeing. With Yonejiro on his deathbed, he finally spoke to Isamu for the first time about his Japanese family. He told them to look after their half-half brother. He passed away in 1947 at the age of 71.

Isamu returned to Japan in 1951 at the age of 45. He married Yoshiko Yamaguchi (known as Ri Koran in China and Shirely Yamaguchi in America), a famous Japanese singer born in Manchuria, that same year. According to Eri Hotta, as someone who was Japanese but grew up in China, she felt torn between two identities. Yamaguchi wrote that she was attracted to Isamu as someone else who was torn between two identities. They broke up four years later in 1955 with Yamaguchi being quoted saying that Isamu was too American.

View this post on Instagram

During their marriage, Isamu took it upon himself to design a cenotaph for the Atomic bomb in Hiroshima. As someone who was mixed Japanese and American he hoped to be a symbol of democracy and peace in the future. However, ‘Memorial to the Dead, Hiroshima’ was never realised in light of being American. The memorial cenotaph was designed by Pritzker Prize winning Japanese architect Kenzo Tange.

Once again feeling a sense of alienation in Japan, Isamu set off on another world trip that saw him sculpt and design art all around the world. Notable works include the Gardens for UNESCO in Paris (1956), many instillations around America, a sculpture garden in Jerusalem, Israel, and World Expo ’70 Fountains in Osaka. His final work which opened in 2004 in Sapporo, Japan was designed in 1988, shortly before his death.

A Citizen of the Earth

Through his stone sculptures we are able to see Isamu’s profound enthusiasm for the medium. Throughout his life he was drilling, chipping, and shaping mostly resistant, unalterable objects. As he grew older the evolution in his stone sculptures was also apparent. We saw more ‘natural’ looking sculptures. Almost as if he accepted that somethings cannot be forced. By the time of his death in 1988 he had received a National Medal of Arts from US President Ronald Reagan (June 1987) and the Order of the Scared Treasure from the Japanese government (1988). The highest acknowledgement from the two governments from which Isamu was: Japanese and American. But Isamu Noguchi was heard often declaring these words: “I just want to be a citizen of the world.”